Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital (ZSFGH) is a city within a city—a dense, vertical campus with constant foot traffic, high-acuity medicine, psychiatric emergencies, and complex social-service needs moving through the same corridors. Vulnerable inpatients can’t “opt out” of that environment. They can’t leave when violence erupts. They depend on the hospital’s security posture to be strong, visible, and fast.

Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital (ZSFGH) is a city within a city—a dense, vertical campus with constant foot traffic, high-acuity medicine, psychiatric emergencies, and complex social-service needs moving through the same corridors. Vulnerable inpatients can’t “opt out” of that environment. They can’t leave when violence erupts. They depend on the hospital’s security posture to be strong, visible, and fast.

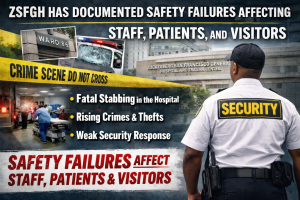

ZSFGH has documented safety failures affecting staff, patients, and visitors—and the public record shows those failures are not hypothetical.

ZSFGH is a high-risk campus, not an outpatient clinic

ZSFGH is San Francisco’s only Level-1 Trauma Center and a major hub for psychiatric emergency care and high-risk patient volume. That reality alone demands a district-style security posture—the kind you would expect for a downtown transit node, a courthouse complex, or a busy police district footprint.

DPH’s own planning direction: reduce sworn presence, measure “success” by avoiding law enforcement

DPH’s security planning materials have repeatedly centered a policy goal of reducing the presence of law enforcement, and DPH has emphasized metrics framed around completing Behavioral Emergency Response Team (BERT) interventions without law enforcement present. SF Media

DPH’s own Environment of Care reporting also describes BERT as part of a broader strategy to reduce reliance on law enforcement—explicitly listing measures of “success” such as reducing law-enforcement interventions and “replacing” deputy positions with DPH security roles.

BERT may help in some situations. But a hospital campus does not become “safe” because sworn staff were avoided. It becomes safe when violence is prevented, contained quickly, deterred, and when vulnerable people are protected in real time.

The December 2025 Ward 86 killing: the public timeline shows warning signs — and the system still failed

In December 2025, a social worker at Ward 86 was fatally stabbed inside ZSFGH. Reporting after the killing describes long-standing safety concerns, prior warnings, and a security posture that did not stop a determined attacker. San Francisco Chronicle

Mission Local’s reported timeline (source: Mission Local)

Mission Local reported that the alleged attacker had been reported to security for abusive behavior and threats toward a doctor about two weeks before the attack, that there were plans to ban him, and that staff had tried to contact him leading up to the incident. (Mission Local also reports eyewitness accounts disputing the “within seconds” narrative and describes delays and gaps in control of access and response.)

That matters because it goes directly to a second issue:

DPH’s own Violence Risk Notification Policy: if a high-risk threat is identified, law enforcement notification is required

DPH’s Violence Risk Notification Policy contemplates situations where a threat is assessed and escalated, and it includes explicit notification requirements that involve law enforcement. The policy’s notification flow requires SFSO notification and indicates SFPD notification as part of the process when certain thresholds are met.

If DPH leadership had credible notice of a specific, escalating, high-risk threat (as Mission Local reports), then the core question becomes unavoidable:

Did DPH follow its own violence-risk notification policy—early, formally, and fully—so that sworn resources could be deployed in a preventive posture (not merely reactionary)?

When a system trains itself—by policy design, incentives, and staffing—to treat sworn presence as something to be minimized, deputies risk being pushed into a reactionary role, and then blamed when the underlying security posture fails.

ZSFGH’s own security reporting shows serious crime and safety volume

DPH/SFHN security reporting for ZSFGH documents significant incident volume across categories that directly affect staff, patients, and visitors. In the FY 2023–2024 security annual report, ZSFGH reported hundreds of “crimes against persons,” along with property crimes and other categories (including increases compared to prior years in multiple areas).

This is not an abstract debate about ideology. It’s measurable security workload on a high-risk campus.

Documented theft, privacy loss, and property vulnerability — not just violence

Safety is not only stabbings. It’s also the predictable results of weak deterrence and insufficient patrol coverage in a “city-within-a-city” environment:

-

Attempted theft of emergency equipment from an ambulance at ZSFGH in September 2024 resulted in a paramedic injury during the incident. San Francisco Chronicle+1

-

A missing patient logbook containing sensitive information triggered security and policy review reporting in April 2024. SFist

And as our current article correctly emphasizes: we haven’t even fully touched the broader theft exposure—including the vulnerability of hospital-owned property, supplies, and equipment, and the diversion risk that grows when visible deterrence and real patrol saturation are reduced.

What a working, realistic fix looks like (short and operational — not a “theory document”)

ZSFGH needs district-style coverage that matches the threat environment, not a model optimized around avoiding sworn presence:

-

Uniformed deputy foot patrols across corridors, stairwells, entrances, elevators, and transition points (deterrence + rapid response).

-

Plainclothes deputies on campus in addition to assigned posts, focused on:

-

catching theft and criminal activity without telegraphing presence, and

-

co-responding with BERT when appropriate—while preserving immediate peace-officer capability when violence erupts.

-

-

A posture that treats sworn staffing as preventive protection for staff, patients, and visitors—not a last-second backstop.

Bottom line

The public record now includes a fatal stabbing inside ZSFGH, documented concerns about long-running safety failures, and ongoing theft/property vulnerabilities. San Francisco Chronicle+2San Francisco Chronicle+2 Meanwhile, DPH’s own planning materials and internal reporting show a model and culture shift aimed at reducing law-enforcement presence and measuring “success” by minimizing law-enforcement involvement. SF Media

ZSFGH is not safe for vulnerable patients under the current posture—nor is it reliably safe for staff and visitors. The standard must be real protection and real outcomes—not metrics that celebrate how often deputies were avoided.